A conversation with OpenAI’s first artist in residence

Alex Reben makes art with (and about) AI. I talked to him about what the new wave of generative models means for the future of human creativity.

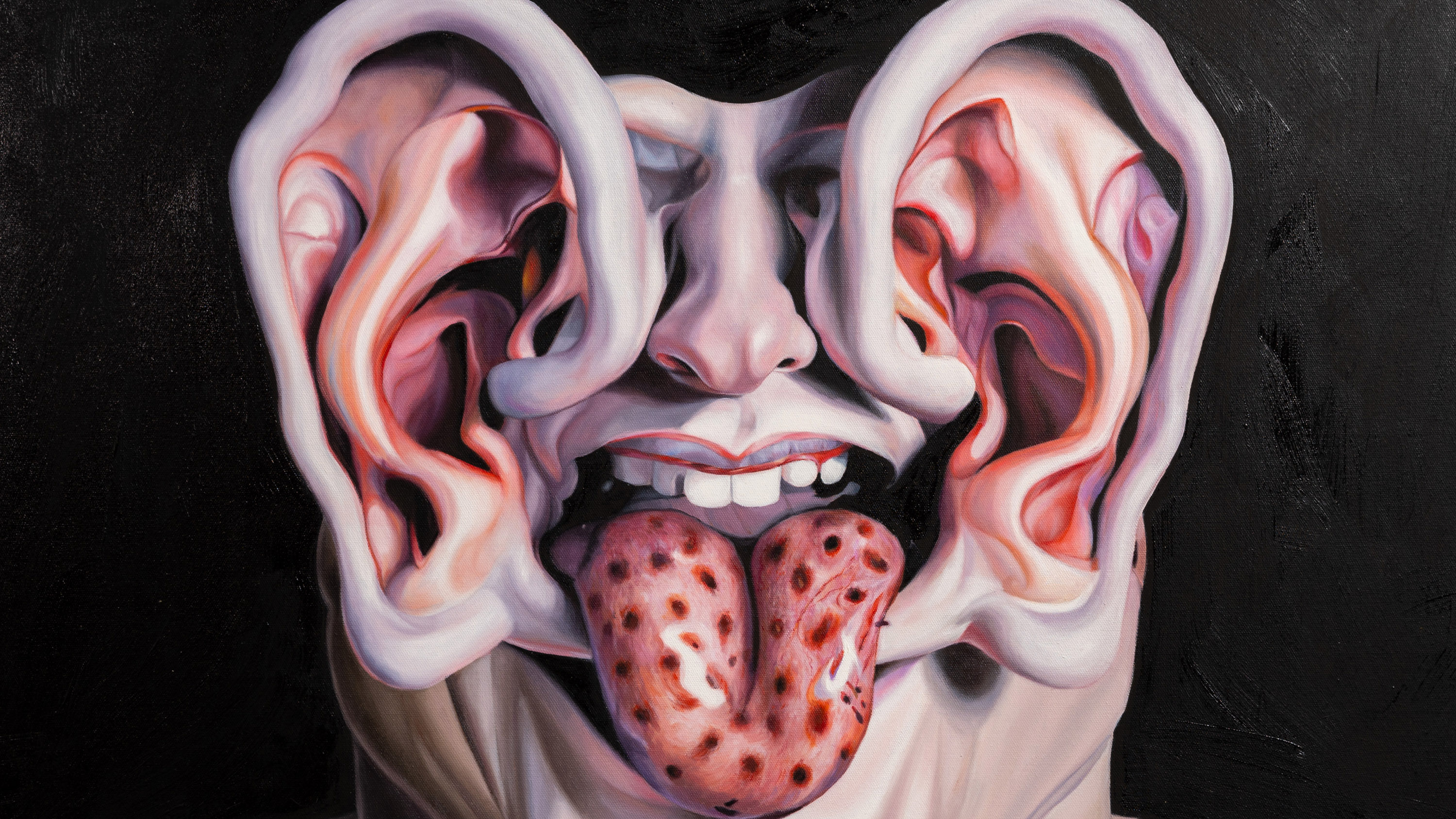

Alex Reben’s work is often absurd, sometimes surreal: a mash-up of giant ears imagined by DALL-E and sculpted by hand out of marble; critical burns generated by ChatGPT that thumb the nose at AI art. But its message is relevant to everyone. Reben is interested in the roles humans play in a world filled with machines, and how those roles are changing.

“I kind of use humor and absurdity to deal with a lot of these issues,” says Reben. “Some artists may come at things head-on in a very serious manner, but I find if you’re a little absurd it makes the ideas more approachable, even if the story you’re trying to tell is very serious.”

Reben is OpenAI’s first artist in residence. Officially, the appointment started in January and lasts three months. But Reben’s relationship with the San Francisco–based AI firm seems casual: “It’s a little fuzzy, because I’m the first, and we’re figuring stuff out. I’m probably going to keep working with them.”

In fact, Reben has been working with OpenAI for years already. Five years ago, he was invited to try out an early version of GPT-3 before it was released to the public. “I got to play around with that quite a bit and made a few artworks,” he says. “They were quite interested in seeing how I could use their systems in different ways. And I was like, cool, I’d love to try something new, obviously. Back then I was mostly making stuff with my own models or using websites like Ganbreeder [a precursor of today’s generative image-making models].”

In 2008, Reben studied math and robotics at MIT’s Media Lab. There he helped create a cardboard robot called Boxie, which inspired the cute robot Baymax in the movie Big Hero 6. He is now director of technology and research at Stochastic Labs, a nonprofit incubator for artists and engineers in Berkeley, California. I spoke to Reben via Zoom about his work, the unresolved tension between art and technology, and the future of human creativity.

Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

You’re interested in ways that humans and machines interact. As an AI artist, how would you describe what you do with technology? Is it a tool, a collaborator?

Firstly, I don’t call myself an AI artist. AI is simply another technological tool. If something comes along after AI that interests me, I wouldn’t, like, say, “Oh, I’m only an AI artist.”

Okay. But what is it about these AI tools? Why have you spent your career playing around with this kind of technology?

My research at the Media Lab was all about social robotics, looking at how people and robots come together in different ways. One robot [Boxie] was also a filmmaker. It basically interviewed people, and we found that the robot was making people open up to it and tell it very deep stories. This was pre-Siri, or anything like that. These days people are familiar with the idea of talking to machines. So I’ve always been interested in how humanity and technology co-evolve over time. You know, we are who we are today because of technology.

Right now, there’s a lot of pushback against the use of AI in art. There’s a lot of understandable unhappiness about technology that lets you just press a button and get an image. People are unhappy that these tools were even made and argue that the makers of these tools, like OpenAI, should maybe carry some more responsibility. But here you are, immersed in the art world, continuing to make fun, engaging art. I’m wondering what your experience of those kinds of conversations has been?

Yeah. So as I’m sure you know, being in the media, the negative voices are always louder. The people who are using these tools in positive ways aren’t quite as loud sometimes.

But, I mean, it’s also a very wide issue. People take a negative view for many different reasons. Some people worry about the data sets, some people worry about job replacement. Other people worry about, you know, disinformation and the world being flooded with media. And they’re all valid concerns.

When I talk about this, I go to the history of photography. What we’re seeing today is basically a parallel of what happened back then. There are no longer artists who paint products for a living—like, who paint cans of peaches for an advertisement in a magazine or on a billboard. But that used to be a job, right? Photography eliminated that swath of folks.

You know, you used the phrase—I wrote it down—“just press a button and get an image,” which also reminds me of photography. Anyone can push a button and get an image, but to be a fine-art photographer, it takes a lot of skill. Just because artwork is quick to make doesn’t necessarily mean it’s any worse than, like, someone sculpting something for 60 years out of marble. They’re different things.

AI is moving fast. We’ve moved past the equivalent of wet-plate photography using cyanide. But we’re certainly not in the Polaroid phase quite yet. We’re still coming to terms with what this means, both in a fine-art sense but also for jobs.

But, yeah, your question has so many facets. We could pick any one of them and go at it. There’s definitely a lot of valid concerns out there. But I also think looking at the history of technology, and how it’s actually empowered artists and people to make new things, is important as well.

There’s another line of argument that if you have a potentially infinite supply of AI-generated images, it devalues creativity. I’m curious about the balance you see in your work between what you do and what the technology does for you. How do you relate that balance to this question of value, and where we find value in art?

Sure, value in art—there’s an economic sense and there’s a critical sense, right? In an economic sense, you could tape a banana to a wall and sell it for 30,000 dollars. It’s just who’s willing to buy it or whatever.

In a critical sense, again, going back to photography, the world is flooded with images and there are still people making great photography out there. And there are people who set themselves apart by doing something that is different.

I play around with those ideas. A little bit like—you know, the plunger work was the first one. [The Plungers is an installation that Reben made by creating a physical version of an artwork invented by GPT-3.] I got GPT to describe an artwork that didn’t exist; then I made it. Which kind of flips the idea of authorship on his head but still required me to go through thousands of outputs to find one that was funny enough to make.

Back then GPT wasn’t a chatbot. I spent a good month coming up with the beginning bits of texts—like, wall labels next to art in museums—and getting GPT to complete them.

I also really like your ear sculpture, Ear we go again. It’s a sculpture described by GPT-3, visualized by DALL-E, and carved out of marble by a robot. It’s sort of like a waterfall, with one kind of software feeding the next.

When text-to-image came out, it made obvious sense to feed it the descriptions of artworks I’d been generating. It’s a chain, sort of back and forth, human to machine back to human. That ear, in particular: it starts with a description that’s fed into DALL-E, but then that image was turned into a 3D model by a human 3D artist.

And after that it was carved by robots. But the robots get only so far with the detail, so human sculptors have to come in and finish it by hand. I’ve made 10 or 15 permutations of this, playing with those back-and-forths, chaining technology together. And the final thing that happens now is that I will take a picture of the artwork and get GPT-4 to create the wall label for it.

Yeah, that keeps coming up in your work, the different ways that humans and machines interact.

You know, I made some videos of the process of these things being made to show how many artisans were employed in making them. There are still huge industries where I can see AI increasing work for folks, people who will make stuff that AI comes up with.

I’m struck by the serendipity that often comes with generative tools, making art out of something random. Do you see a connection between your work and found art or ready-mades, like Duchamp’s Fountain? I mean, you're maybe not just coming across a urinal and thinking, “Oh, that's cool.” But when you play around with these tools, at some point you must get something presented to you that you react to and think, “I can use that.”

For sure. Yeah, it actually reminds me a little bit more of street photography, which I used to do when I was in college in New York City, where you would just kind of roam around and wait for something to inspire you. Then you’d set yourself up to capture the image in the way that you wanted. It’s kind of like that for sure. There’s definitely a curatorial process to it. There’s a process of finding things, which I think is interesting.

We talked about photography. Photography changed the art that came after it. You know, you had movements where people wanted to try to get at a reality that wasn’t photographic reality—things like Impressionism, and Cubism or Picasso. Do you think we’ll see something similar happening because of AI?

I think so. Any new artistic tool definitely changes the field as people figure out not only how to use that tool but how to differentiate themselves from what that tool can do.

Talking of AI as a tool—do you think that art will always be something made by humans? That no matter how good the tech gets, it will always just be a tool? You know, the way you’ve strung together these different AIs—you could do that without being in the loop. You could just have some kind of curator AI at the end that chooses what it likes best. Would that ever be art?

I actually have a couple of works in which an AI creates an image, uses the image to create a new image, and just keeps going. But I think even in a super-automated process you can go back far enough to find some human somewhere who made a decision to do something. Like, maybe they chose what data set to use.

We might see hotel rooms filled with robot paintings. I mean, stuff we hardly even look at, that never even makes its way through human curation.

I guess the question is really how much human involvement is needed to make something art. Is there a threshold or, like, a percentage of involvement? It’s a good question.

Yeah, I guess it’s like, is it still art if there’s no one there to see it?

You know, what is and isn’t art is one of those questions that has been asked forever. I think more to the point is: What is good art versus bad art? And that’s very personal.

But I think humans are always going to be doing this stuff. We will still be painting in the far future, even when robots are making paintings.

Deep Dive

Artificial intelligence

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

OpenAI teases an amazing new generative video model called Sora

The firm is sharing Sora with a small group of safety testers but the rest of us will have to wait to learn more.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Responsible technology use in the AI age

AI presents distinct social and ethical challenges, but its sudden rise presents a singular opportunity for responsible adoption.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.