Tech Slowdown Threatens the American Dream

Things Reviewed

The Rise and Fall of American Growth

By Robert J. Gordon

Princeton University Press, 2016"Is Innovation Over? The Case Against Pessimism"

By Tyler Cowen

Foreign Affairs, March/April 2016

In a three-month period at the end of 1879, Thomas Edison tested the first practical electric lightbulb, Karl Benz invented a workable internal-combustion engine, and a British-American inventor named David Edward Hughes transmitted a wireless signal over a few hundred meters. These were just a few of the remarkable breakthroughs that Northwestern University economist Robert J. Gordon tells us led to a “special century” between 1870 and 1970, a period of unprecedented economic growth and improvements in health and standard of living for many Americans.

Growth since 1970? “Simultaneously dazzling and disappointing.” Think the PC and the Internet are important? Compare them with the dramatic decline in infant mortality, or the effect that indoor plumbing had on living conditions. And the explosion of inventions and resulting economic progress that happened during the special century are unlikely to be seen again, Gordon argues in a new book, The Rise and Fall of American Growth. Life at the beginning of the 100-year period was characterized by “household drudgery, darkness, isolation, and early death,” he writes. By 1970, American lives had totally changed. “The economic revolution of 1870 to 1970 was unique in human history, unrepeatable because so many of its achievements could happen only once,” he writes.

The book attempts to directly refute the views of those Gordon calls “techno optimists,” who think we’re in the midst of great digital innovations that will redefine our economy and sharply improve the way we live. Nonsense, he says. Just look at the economic data; there is no evidence that such a transformation is occurring.

For most Americans, wages are just not keeping up. Incomes actually shrank between 1972 and 2013. And it’s not going to get any better, predicts Robert Gordon.

Indeed, productivity growth, which allows companies and nations to expand and prosper—and, at least potentially, allows workers to earn more money—has been dismal for more than a decade. Although it might seem as though a lot of innovation is going on, “the [productivity] slowdown is real,” John Fernald, an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, told me. In a recent paper, Fernald and his colleagues traced the sluggishness back to around 2004 and found that the last five years saw close to the slowest productivity growth ever measured in the United States (the data go back to the late 1800s). And Fernald says technology and innovation are “a big part of the story.” Some techno optimists have argued that the full benefits of apps, cloud computing, and social media are not showing up in the economic measurements. But even if that’s true, their overall effect is not all that significant. Fernald found that any growth spurred by such digital advances has been inadequate to overcome the lack of broader technological progress.

Gordon is not the first economist to be unimpressed by today’s digital technologies. George Mason University’s Tyler Cowen, for one, published The Great Stagnation in 2011, warning that apps and social media were having limited economic impact. But Gordon’s book is notable for contrasting today’s slowdown with the radical and impressive gains of the first three-quarters of the century. Over the course of more than 750 pages, he describes how American lives were changed by everything from the electrification of homes to the ubiquity of household appliances to the construction of extensive subway systems in New York and other cities to medical breakthroughs such as the discovery of antibiotics.

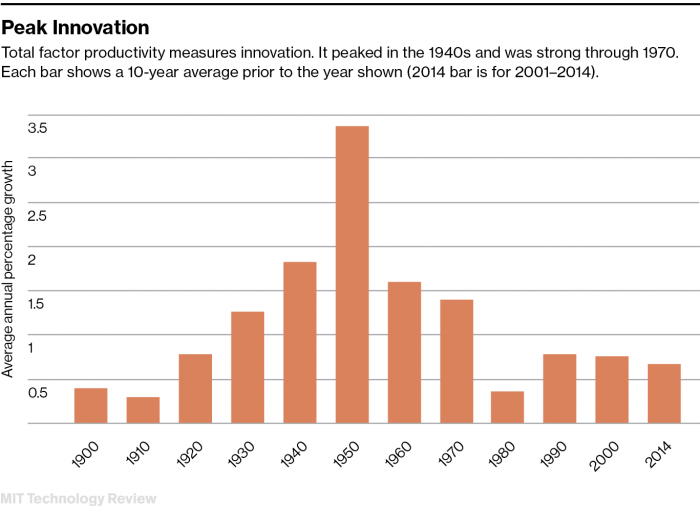

In some ways, though, the most compelling and ominous story is the one that Gordon tells through the numbers. Economists typically define productivity as how much workers produce in an hour. It depends on the contributions of capital (such as equipment and software) and labor; people can produce more if they have more tools and more skills. But improvements in those areas don’t account for all productivity increases over time. Economists chalk up the rest to what they call “total factor productivity.” It’s a bit of a catchall for everything from new types of machines to more efficient business practices; but, as Gordon writes, it is “our best measure of the pace of innovation and technical progress.”

Between 1920 and 1970, American total factor productivity grew by 1.89 percent a year, according to Gordon. From 1970 to 1994 it crept along at 0.57 percent. Then things get really interesting. From 1994 to 2004 it jumped back to 1.03 percent. This was the great boost from information technology—specifically, computers combined with the Internet—and the ensuing improvements in how we work. But the IT revolution was short-lived, argues Gordon. Today’s smartphones and social media? He is not overly impressed. Indeed, from 2004 to 2014, total factor productivity fell back to 0.4 percent. And there, he concludes, we are likely to remain, with technology progressing at a rather sluggish pace and confining us to disappointing long-term economic growth.

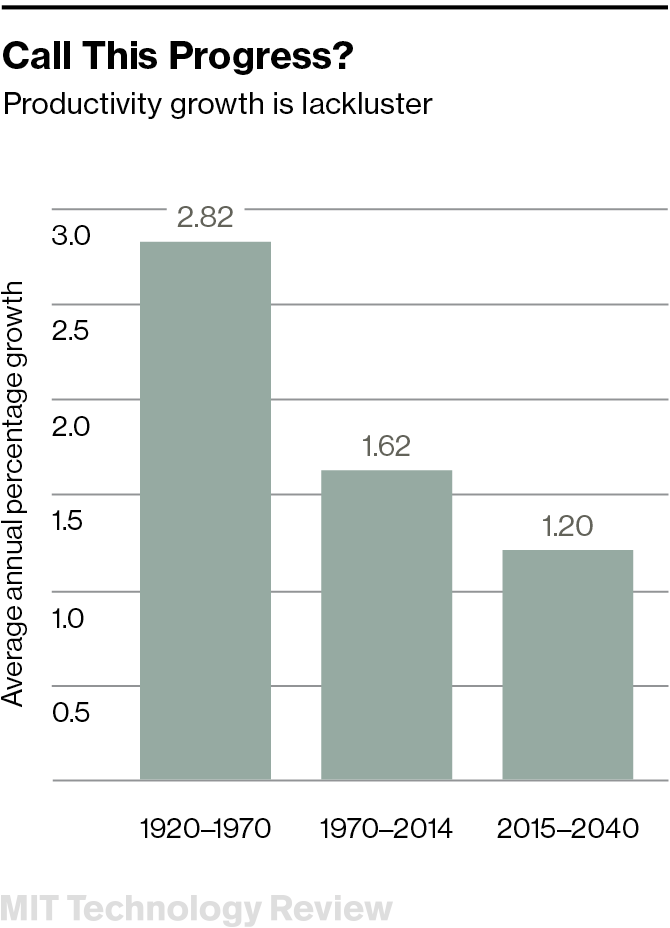

These numbers matter. Such lackluster productivity growth precludes the kind of rapid economic expansion and improvements in the standard of living that Gordon describes happening in the mid-20th century. The lack of strong productivity to fuel economic growth—combined with what Gordon calls the “headwinds” facing the country, such as rising inequality and sagging levels of education—helps explain the financial pain felt by many. For most Americans, wages are just not keeping up. Except for the very top earners, real incomes actually shrank between 1972 and 2013. And it’s not going to get any better, says Gordon. He predicts that median disposable income will grow at a bleak 0.3 percent per year through 2040.

Make America great again

No wonder so many Americans are upset. They sense they will never be as financially secure as their parents or grandparents—and, even more troubling to some, that their children will also struggle to get ahead. Gordon is telling them they are probably right.

If robust economic progress in the first half of the 20th century helped create a national mood of optimism and faith in progress, have decades of much slower productivity growth helped create an era of malaise and frustration? Gordon provides little insight into that question, but there are clues all around us.

Anger over the economy is certainly manifesting itself in the current presidential election. The leading Republican candidate is pledging, somewhat abstractly, to “make America great again,” and vaguely similar sentiments reflecting nostalgia for past prosperity are being echoed in the Democratic campaigns—particularly in Bernie Sanders’s economic plan that purports to achieve productivity growth of 3.1 percent, a level not seen in decades.

There are also hints that the long-term lack of economic growth is affecting some Americans in insidious ways. Late last year, economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton, both at Princeton, described a disturbing trend between 1999 and 2013 among white men aged 45 to 54: an unprecedented rise in morbidity and mortality that reversed years of progress. This group of Americans was experiencing more suicides, drug poisonings, and alcoholism. The reasons are uncertain. But the authors did cautiously offer one possibility: “After the productivity slowdown in the early 1970s, and with widening income inequality, many of the baby-boom generation are the first to find, in midlife, that they will not be better off than were their parents.”

Speculating on how the lack of economic progress has affected the mood of the country is risky. Intense political anger has also broken out during periods of strong growth, such as the 1960s. And today’s economic morass cannot be blamed entirely on poor productivity growth, or even on inequality. Still, could it be that a lack of technological progress is dooming us to a troubled future, even at a time when we celebrate our newest gadgets and digital abilities—and make heroes of our leading technologists?

How do you know?

While Gordon’s willingness to speculate about what lies ahead is one of the strengths of his book, his blanket skepticism about today’s technologies often sounds unjustified, even arbitrary. He dismisses such digital advances as 3-D printing, artificial intelligence, and driverless cars as having limited potential to affect productivity. More broadly, he ignores the potential impact of recent breakthroughs in gene editing, nanotechnology, neurotechnology, and other areas.

You don’t have to be a techno optimist to think that radical and potentially life-changing technologies are not a thing of the past. In “Is Innovation Over?” Tyler Cowen acknowledges the “stagnation in technological progress” but concludes there are ample reasons to be hopeful about the future. Cowen told me: “There are more people working in science than ever before, more science than ever before. In [artificial intelligence], biotechnology, and [treatments] for mental illnesses, you could see big advances. I’m not saying it is going to happen tomorrow—it may be 15 to 20 years from now. But how could you possibly know it won’t happen?”

In some ways, Gordon’s book is a useful counter to the popular view that we’re in the midst of a technology revolution, says Daron Acemoglu, an economist at MIT. “It’s a healthy debate,” he says. “The techno optimists have had too much of a run without being challenged.” Yet, says Acemoglu, it’s hard to accept Gordon’s argument that we’re seeing a slowdown in innovation: “It may well be that these innovations haven’t translated into productivity. But if you look at just the technologies that have been [recently] invented and are close to being implemented over the next five to 10 years, they are amazingly rich. It is just very hard to think we’re in an age of paucity of innovation.” And, says Acemoglu, “to project even further into the future that we’re not going to translate these innovations into productivity growth is not an easy argument to make.”

One of the limitations of Gordon’s book, says Acemoglu, is that it doesn’t explain the origins of innovation, treating it like “manna from heaven.” It is “easy to say productivity comes from innovation,” says Acemoglu. “But where does innovation come from, and how does it affect productivity?”

Whether we’re doomed to a future of tough economic times will be at least partially determined by how we utilize innovation and share the benefits of technology.

Better answers to such questions could help us not only to understand how today’s technical advances might boost the economy but also to make sure we implement these technologies in ways that maximize their economic benefits. Whether we’re doomed to a future of dismal technological progress, and hence tough economic times, will be at least partially determined by how we utilize innovation and share the benefits of technology. Do we invest in the infrastructure that will make the most of driverless cars? Do we provide access to advanced medicine for a broad portion of the population? Do we provide new digital tools to the growing segment of the workforce with service jobs in health care and restaurants, allowing them to be more productive employees?

Gordon could be right; the great inventions of the late 1800s changed lives to an extent that will never be matched. Nor will many of the circumstances that were so conducive to economic progress during that era be seen again. But if we can better understand the potential of today’s innovations—remarkable in themselves—and create the policies and investments that will allow them to be fully and fairly implemented, we will at least have a fighting chance of achieving robust economic progress again.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

OpenAI teases an amazing new generative video model called Sora

The firm is sharing Sora with a small group of safety testers but the rest of us will have to wait to learn more.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.