China’s next cultural export could be TikTok-style short soap operas

These apps are betting on low-budget productions, two-minute episodes, scripts adapted from Chinese web novels, and an aggressive marketing strategy.

Until last year, Ty Coker, a 28-year-old voice actor who lives in Missouri, mostly voiced video games and animations. But in December, they got a casting call for their first shot at live-action content: a Chinese series called Adored by the CEO, which was being remade for an American audience. Coker was hired to dub one of the main characters.

But you won’t find Adored by the CEO on TV or Netflix. Instead, it’s on FlexTV, a Chinese app filled with short dramas like this one. The shows on FlexTV are shot for phone screens, cut into about 90 two-minute episodes, and optimized for today’s extremely short attention span. Coker calls it “soap operas for the TikTok age.”

In the past few years, these short dramas have become hugely popular in China. They often span nearly a hundred episodes, but since each episode is only one or two minutes long, the whole series is no longer than a traditional movie. The most successful domestic productions make tens of millions of dollars in a few days. The entire market of short dramas in China was worth over $5 billion in 2023.

This success has motivated a few companies to try replicating the business model outside China. Not only is FlexTV translating and dubbing shows already released in China, but it has also started filming shows in the US for a more authentically American viewing experience.

It’s easy to compare apps like these to Quibi, a high-profile video service that infamously failed after less than a year in 2020.

But these latest Chinese apps are different. They don’t aim for slick, expensive productions. Instead, they choose simple scripts, shoot an entire series in two weeks, market it heavily online, and move on to the next project if it doesn’t stick.

“The biggest difference between short dramas and films is that they provide different things. We have to analyze the psychological needs of our audience and understand what they want to see … and we try to provide some emotional values,” Xiangchen Gao, the chief operations officer of FlexTV, tells MIT Technology Review.

When a show finds the right audience, it can generate significant revenue in the US too. The top-grossing show on FlexTV can bring in $2 million a week, while the production costs less than $150,000, Wang says.

Several other apps, like ReelShort and DramaBox, are also racing to bring Chinese short dramas to an international audience. They frequently top app stores’ download charts and produce blockbuster shows. Short dramas have been proven to work in China. It’s not always easy to replicate a business model in a different market, but if they succeed, they could be China’s next big cultural export.

The roots in Chinese web novels

Short dramas like Adored by the CEO are often adapted from another cultural product that is distinctly Chinese: web novels.

Web novels are a unique form of literature that has been popular on the Chinese internet for much of the last two decades: long stories that are written and posted chapter by chapter every day. Each chapter can be read in less than 10 minutes, but installments will keep being added for months if not years. Readers become avid fans, waiting for the new chapter to come out every day and paying a few cents to access it.

While some talented Chinese book authors got their big break by writing web novels, the majority of these works are the popcorn of literature, offering daily bite-size dopamine hits. For a while in the 2010s, some found an audience overseas too, with Chinese companies setting up websites to translate web novels into English.

But in the age of TikTok, long text posts have become less popular online, and the web-novel industry is looking to pivot. Business executives have realized they can adapt these novels into super-short dramas. Both forms aim for the same market: people who want something quick to kill time in their commute, or during breaks and lunch.

Many of the leading Chinese short-drama apps today work closely with Chinese web-novel companies. ReelShort is partially owned by COL Group, one of the largest digital publishers in China, with a treasure trove of novels that are ready for adaptation.

To get a quick sense of what these stories are like, you just need to take a look at their titles: President’s Sexy Wife, The Bride of the Wolf King, Boss Behind the Scenes Is My Husband, or The New Rich Family Grudge.

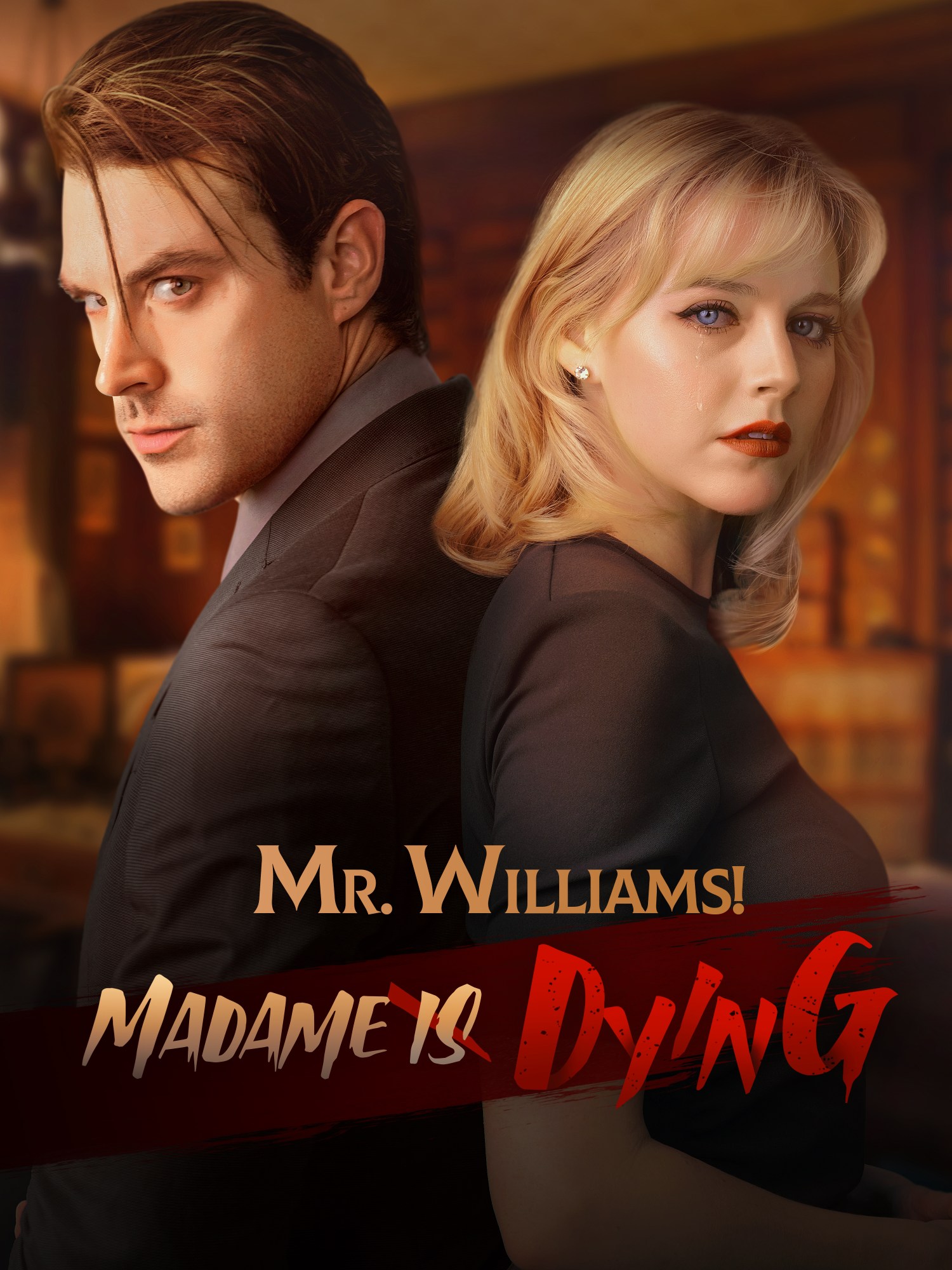

One of the highest-grossing shows on FlexTV is called Mr. Williams! Madame Is Dying. It’s a corny romance story about a love triangle, ultra-rich families, cancer, rebirth, and redemption, and it was adapted from a Chinese web novel that has nearly 1,300 chapters. The original story has been turned into a Chinese short drama, but FlexTV decided to shoot another version in Los Angeles for an international audience.

These short dramas prioritize quick, oversimplified stories of love, wealth, betrayal, and revenge, sometimes featuring mythical creatures like vampires and werewolves. Stories of marrying into a rich family attract men, while stories with a powerful female protagonist in control of her life appeal to women, says Gao, the COO of FlexTV.

“Quibi mostly served the [artistic] pursuits of directors and producers. They thought their tastes were better than the general public and their work was to be appreciated by the elites,” he says, “What we are making is more like fast-moving consumer goods. It’s rooted in the needs of ordinary users.”

Translating the story to a US audience

Still, no matter how universal the plots are, these short dramas need to be adapted to their local audience.

Ty Coker’s work is one example. The character they voiced, a personal assistant to the male protagonist, was named Dawei Hu in the original Chinese production. But in the English dubbing, “Dawei Hu” became “David Hughes.” All the other characters, as well as the geographical references, received similar treatments, while the visuals didn’t change. Sometimes the results of this straightforward swap method are a little jarring. “They would mention: ‘Oh, so and so is coming in from New York. And it was like, okay, I don’t think that character is originally from New York, but we’ll roll with it,” Coker says.

This “Americanization” could make it easier for some viewers to follow and remember the show. “My mom, who watches a lot of soap operas—she’d probably find it easier to follow if everyone has American names,” Coker says. It reminds Coker of anime shows they watched as a child, which would substitute Western names for the Japanese ones.

But that’s not where the localization efforts end. With shows that are later dubbed into a different language, there’s always going to be a feeling of mismatch. That’s why short-drama platforms are now filming their own productions with translated scripts and non-Chinese actors, sometimes even in Hollywood. It costs much more than dubbing an already-made show, but they believe it’s worth it.

FlexTV has just finished filming a new show in Los Angeles. Named Lost in Darkness, it is about a visually impaired woman trying to figure out which of two male characters murdered her father. The production took 10 days in total, with 34 actors filming over 150 scenes. It cost between $150,000 and $200,000.

Roger Chen, a producer of the show, has been instrumental in bringing short dramas to the US. He originally produced traditional-length movies and animations in the States but formed a new company called Purple Filter last year, after noticing the demand for Chinese-adapted stories. His company now coordinates between Chinese platforms and the LA filming industry, scouting actors, directors, and producers who are interested in this new form of content.

He admits these shows can be a hard sell for actors in the US.

“An episode of a short drama is only one and a half minutes long, so the plot buildup is short, if there is any … Actors who are accustomed to traditional scripts find it hard to accept,” Chen says. “But we discovered that it’s necessary to have strong conflicts and quick plot twists. This is the unique content that suits the smartphone medium.”

His company has worked with most of the major platforms, including DramaBox and FlexTV. Meanwhile, there are more and more teams like Chen’s joining the American short-drama industry. “We believe that media content for phones will become a mainstream trend,” he says.

A well-oiled business in targeted ads

The business model of these short dramas is one that American TV audiences are mostly not familiar with. Unlike most American streaming services, which require subscriptions, Chinese platforms for streaming and web novels use a business model of paying by the episode or chapter. Essentially, the first 10 or so episodes are always available for free, but once users are hooked, they need to pay a certain amount to watch each episode. It resembles the microtransaction mechanism in mobile games, which Chinese companies, like the developer of the global hit Genshin Impact, also perfected. Users can quickly rack up thousands in payments by buying small items in-game here and there.

FlexTV has a similar tactic. You can pay $5 for 500 in-app coins, which in return unlock about seven episodes. A whole series therefore can cost around $50, but there are also small tasks users can do in the app to earn free rewards, like watching ads, posting about the app on social media, and doing daily check-ins.

Evidently, some people are willing to pay, as some of these shows are starting to see serious revenues. Gao shares that Mr. Williams! Madame Is Dying is bringing in over $2 million in user payments a week. Similar apps have also reported significant revenues. ReelShort made $22 million in December 2023, the company told the Wall Street Journal, and its global download count has already surpassed that of the ill-fated Quibi.

But there’s a caveat: these phenomenal numbers are also driven by heavy ad spending, which is an essential part of the business model. While it’s cheap to make these shows (around $150,000 per show if filmed in the US), millions of dollars are then spent on pushing them to prospective audiences. For Mr. Williams! Madame Is Dying, for example, the company had to spend $1 million on ads to get over $2 million in revenues.

FlexTV relies on targeted advertising through major platforms like Google, Meta, and TikTok. These platforms allow them to choose what kind of audience they want the ads to impress. For Mr. Williams! Madame Is Dying, FlexTV targeted “young women between the ages of 20 and 40, who like romance content and reading,” says Gao.

For each dollar spent on advertising, the target return on investment is at least $1.30 to $1.50, says Gao. The viral popularity of short dramas in China is no accident but the result of a well-oiled digital marketing industry that has adjusted to the TikTok age.

Despite early successes, the short-drama business inside China is now starting to run into difficulties. As its popularity grows, the Chinese government has started to censor it much as it does the film and TV industry. In a three-month period ending in February 2023, the government banned 25,300 short-drama series (totaling 1.3 million episodes) for being too violent, too sexually suggestive, or too trashy. Chinese short-video platforms like Douyin and Kuaishou have since been routinely removing shows or restricting their producers from buying targeted ads.

This is also part of the reason why companies like ReelShort and FlexTV are looking to expand in foreign markets, where the risks of censorship are much lower. The short-drama industry in the US is akin to what it was like in China in 2021, says Gao, which means there’s little competition and plenty of room to grow. The company plans to produce shows in six languages in the future, but North America will remain its most important market.

Ultimately, they’re betting that these dopamine-inducing mini soap operas will appeal to audiences regardless of their culture or language. “We don’t think Chinese and American audiences have fundamental differences in taste,” Gao says. “Chinese web novels have studied human nature deeply, and they do a great job at evoking emotions. Scriptwriters and directors who excelled in China can capture everyone’s universal desires.”

Deep Dive

Culture

Meet the divers trying to figure out how deep humans can go

Figuring out how the human body can withstand underwater pressure has been a problem for over a century, but a ragtag band of divers is experimenting with hydrogen to find out.

The tech that helps these herders navigate drought, war, and extremists

Shiny, high-tech solutions often miss the mark. Can a simpler data-distribution project be the answer?

Why Threads is suddenly popular in Taiwan

During Taiwan’s presidential election, Meta’s social network emerged as a surprise hit.

Threads is giving Taiwanese users a safe space to talk about politics

But Meta's discomfort with political content could end up pushing them away.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.